Tending

I’m two days away from the end of a month-long residency in North Adams, Massachusetts. It is an intimate and quiet residency, just you and one other resident in the home of artis Carolyn Clayton and artist blacksmith Ben Westbrook. Walkaway House is a former dentist office and, further back, a funeral parlour. The residency is named the Tend Residency.

Tend: to care for or look after; give one's attention to.

An appropriately named residency for me right now.

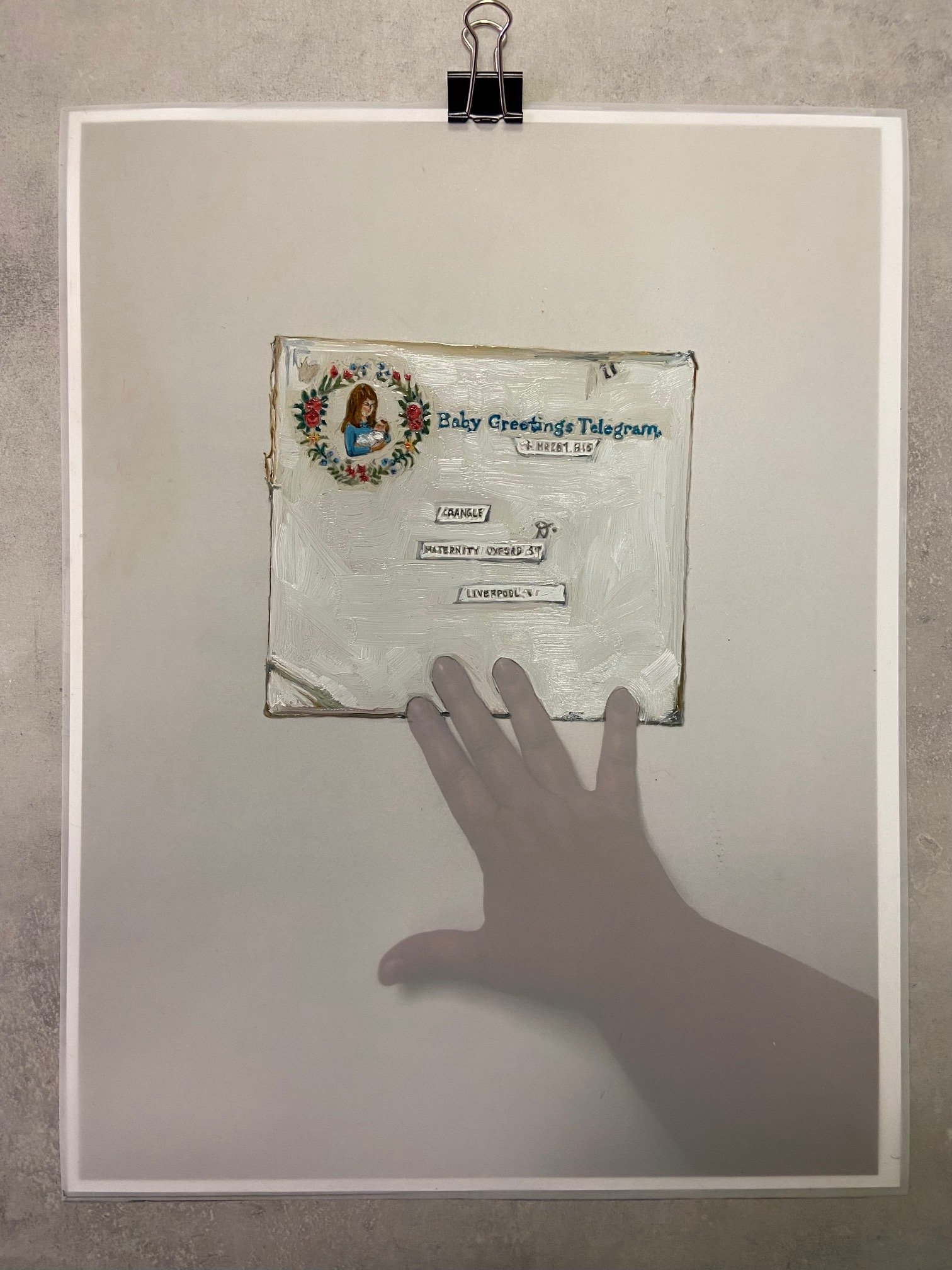

Just five months after my mother passed away in November, my father died suddenly in April. There were several weeks of the practical work of death, culminating in a celebration of life for my father on June 3. Seven days later, I was in Walkaway House, unpacking emotionally charged ephemera from my parents’ home, ready to do the other work of death, the slippery work of grieving. This work is not linear, there are no concrete tasks to scratch off one's to-do list and there is no sense of culmination or completion.

My live/work space at Walkaway House is called the Looking Glass Room; there is a massive mirror over a fireplace. I taped my parents’ things to the mirror to be both looking at them and beyond them- seeing my partial reflection in the in-between spaces. In readings done here about grief, I consider the idea that the void opened up by loss leads to transformation (Taryn Simon, The Occupation of Loss). Peering through the papers, slides, and memorabilia on the mirror at my half-reflections, I wondered what changes in my worldview will be exacted by this loss - how will I emerge on the other side of the Looking Glass?

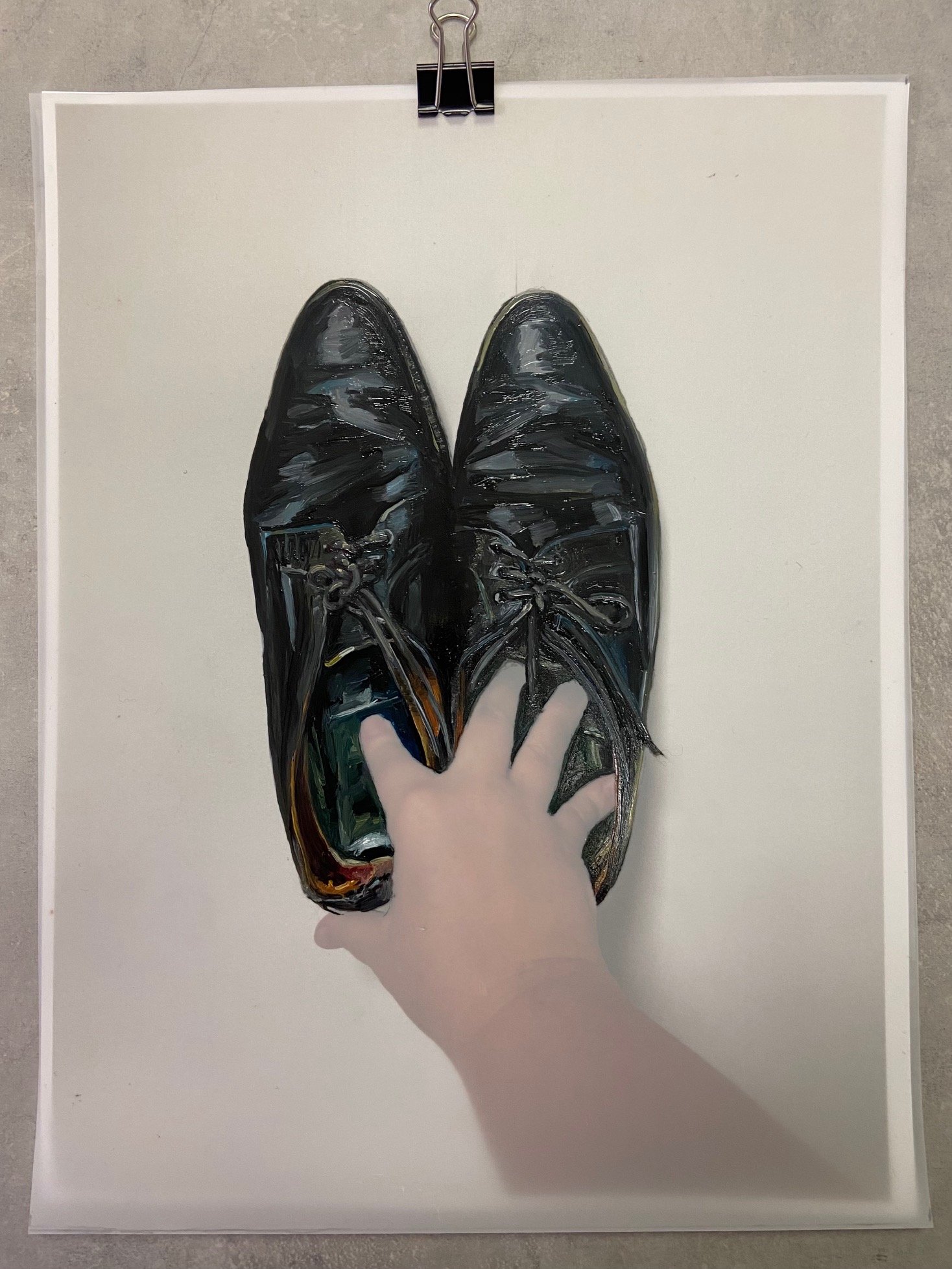

Grief is a chronic confronting of the death, returning to and repeating the moment when someone is no more, that moment of ripping away. I draw my hands holding my father’s still warm hands in the hospital, his empty wedding shoes, and over the four weeks of the residency, the plastic bag of his ashes as I listen to his voice telling his life story, recordings he had started in February. I draw his face from the sketch I made from his body the night he died and complete his corpse with an appropriated body from Holbein’s Dead Christ.

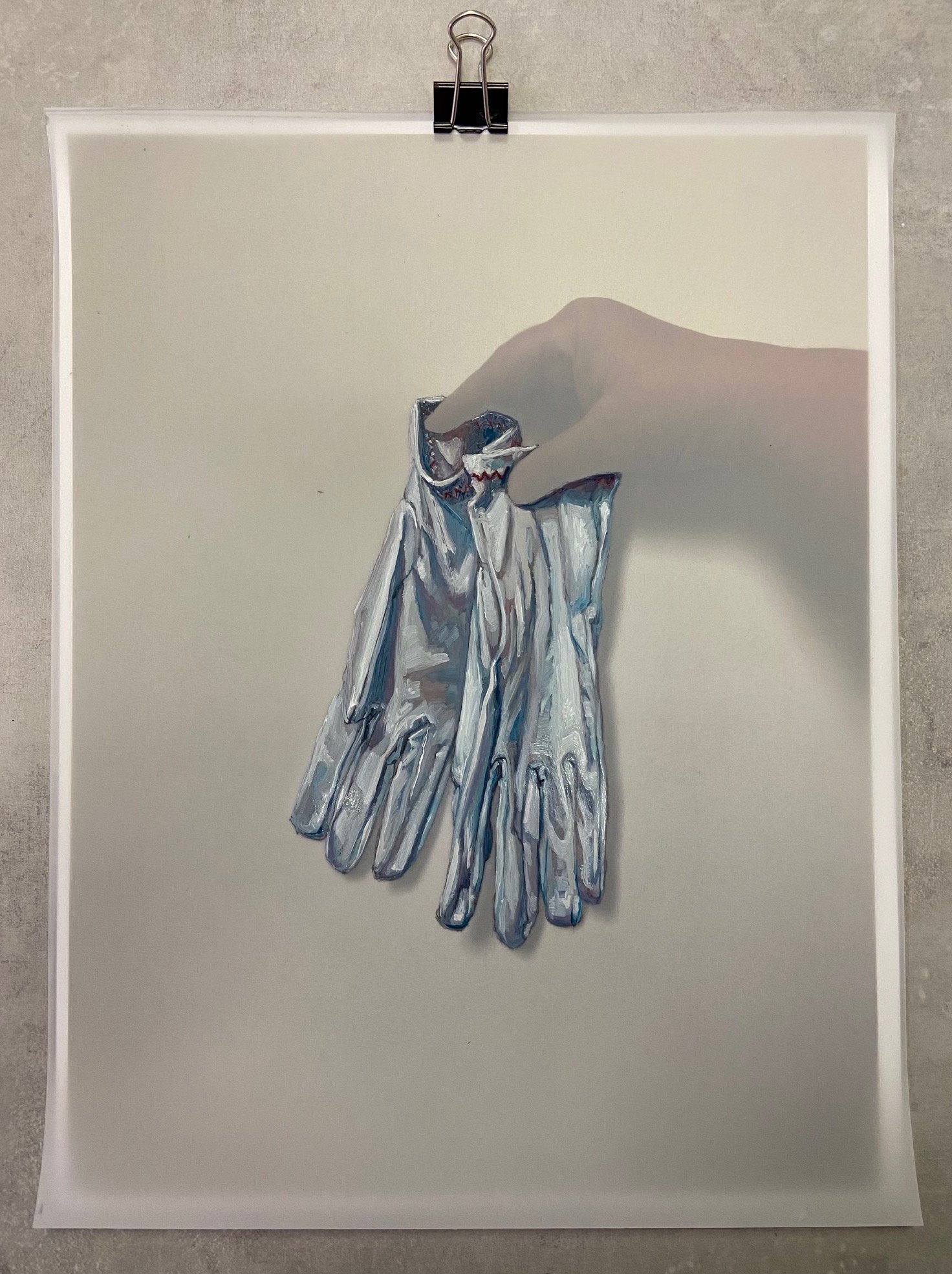

I cover a wall with figures from art history in gestures of lamentation and grief. I try in these gestures on for fit and, recognizing the poses as performative, don a pair of white polyester gloves from an unopened bag of dozens of pairs found in my mother’s closet- a quiet mystery she left behind. I paint these images of myself; I’m still unsure how to handle the gloves.

WIP: performing gestures of grief from art history | each panel 18 x 24“, oil on cradled panel, photo transfer of art historical image

These paintings of figurative gesture are abandoned somewhat, as I turn my focus back to the ephemera I have carted over the border. I find myself considering residual gesture in objects rather than gesture as overtly expressed by a figure.

I had torn off the electrocardiograph paper from the heart monitor as I escorted my dad’s body from the emergency room, recognizing it as the last gesture he would make. Connecting to this final, flat thread, I pull his signature from the line. On a whim, I film my hand doing this. I find the video powerful. Playing with it further, I reverse the video and my hand writes his signature and simultaneously erases it. I think of the reading I am doing here- Derrida says, “death severs the name from the bearer of it.”

Video and erasure. I return to the Holbeinesque drawing of my dad and film myself erasing his body, from his feet to his head. In the video, at the near-end, I sob as I erase his mouth and nose. I confront the ripping moment again.

Derrida says that each subsequent death acts as a betrayal to any earlier death; the freshest death becomes the only death. I register a sense of infidelity to my mother’s death. I unroll and install a painting of my mother done at my last residency to reset this feeling. And then, at a coffee shop, I find myself making a gesture so fully my mother’s that I cry: using the pads of my fingers to pick errant sesame seeds off the table. Her gesture is carried in me. I make another video.

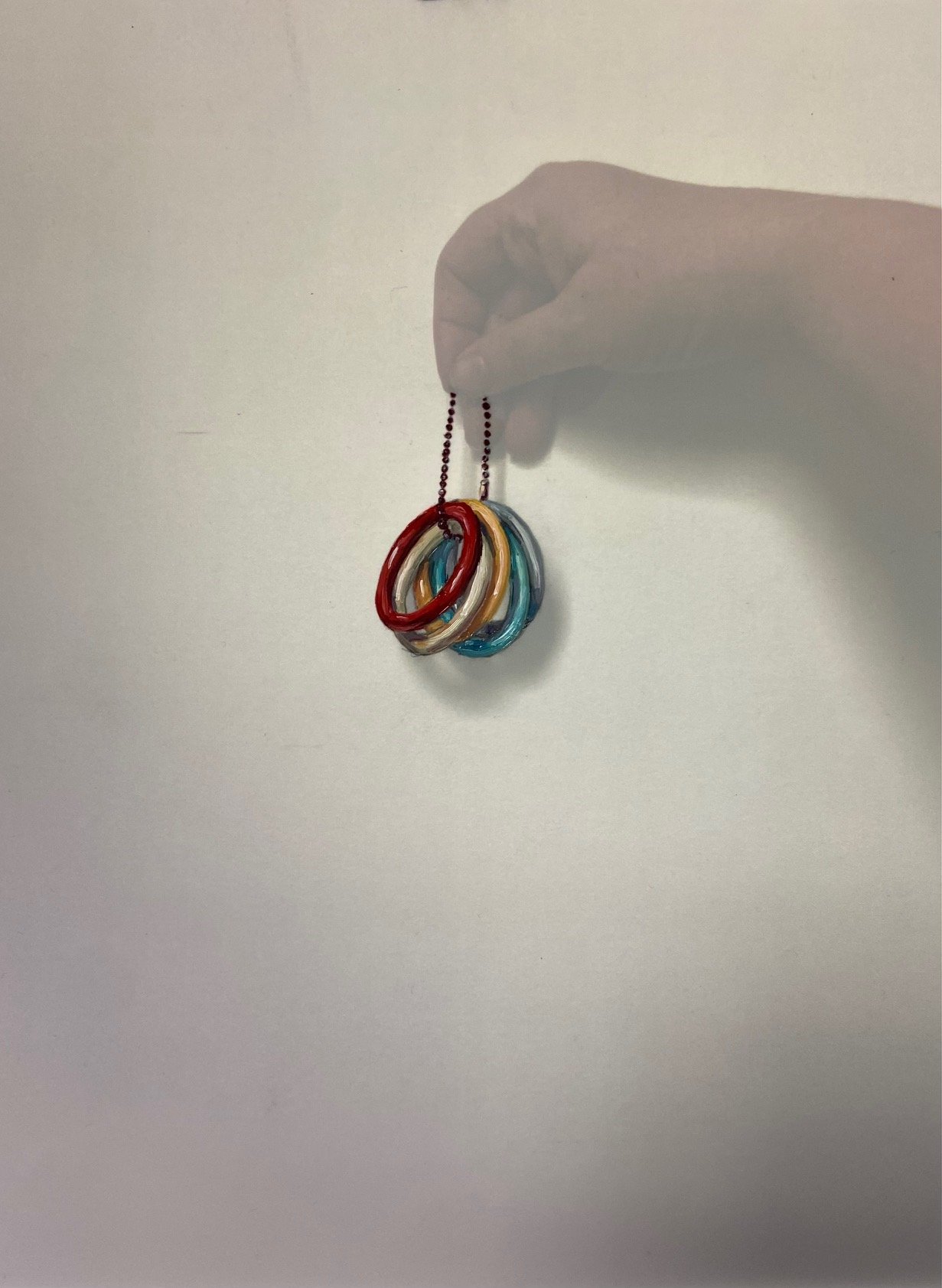

I photograph my hands holding their things, unaware I am beginning to archive the stuff I intend to discard after working with it, my hands where their hands once were. I cover each photograph in Mylar and paint only the object in oil, the care in examining while painting akin to an archival process, crumples and scuffs duly noted. The painted object is oily and unctuous, my hand is ghostly.

There is more, much more. I will continue to step in and out of grief, like an emotional Hokey Pokey dance. But I am grateful for this brief and tender time at Walkaway House.